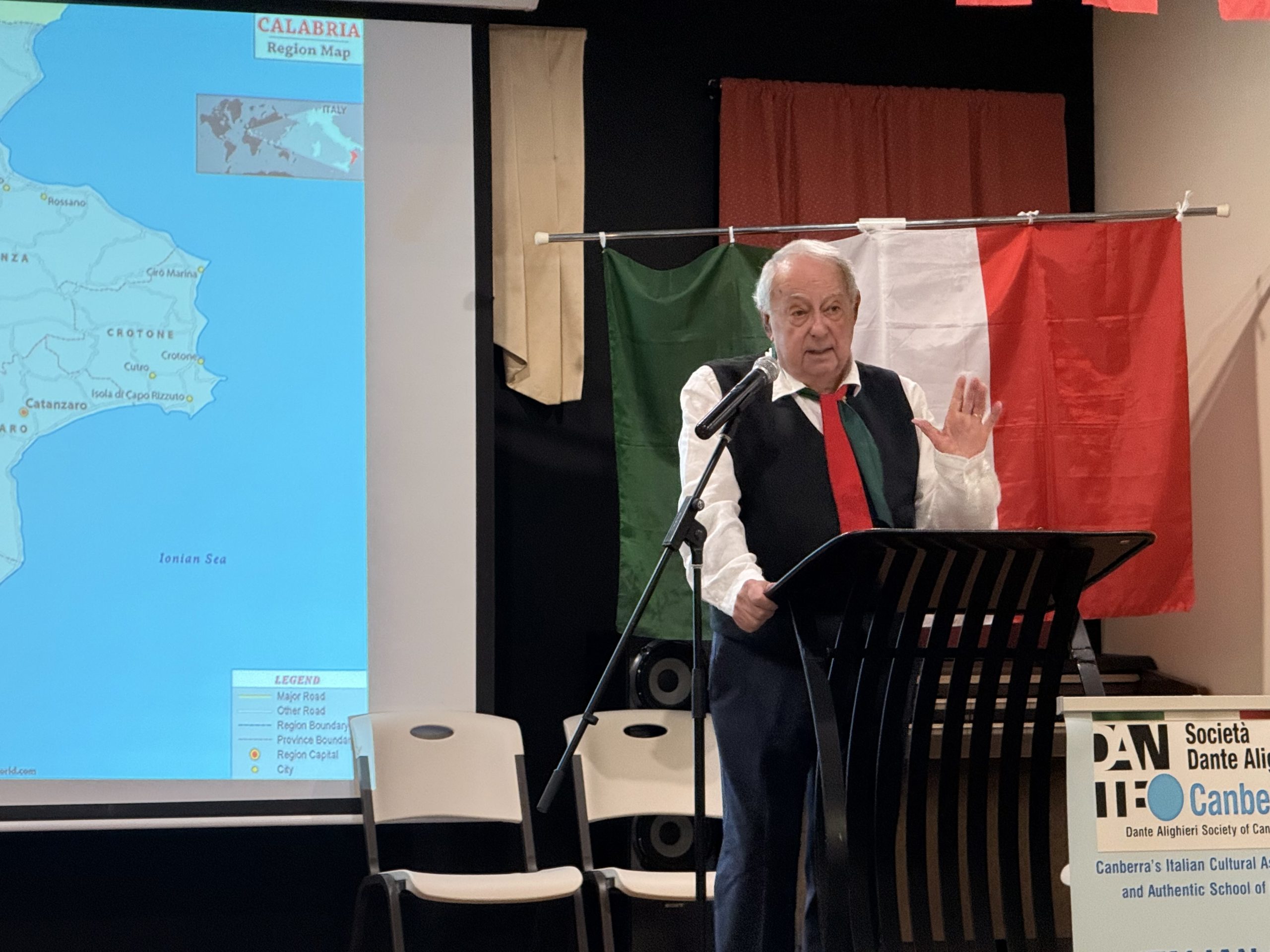

On the initiative of the Dante Vice President, Jo Bisa, a “Cultura e Cucina” event was held in the Cultural Centre on the evening of 27thof June, 2025. About one hundred guests attended, including the Cultural Attache of the Embassy of Italy, Professoressa Valentina Biguzzi, and the President of the Federation of Calabresi, Vincenzo Ciano. Dante President Francesco Papandrea and several committee members were also present.

The “cucina” part of the event included a presentation on Calabrese food and wine by Josephine Gagliardi-Gregoire and her husband Christophe Gregoire. Complimentary wines were courtesy of Calabria Family Wines. The Musica Viva Choir of the Dante opened the evening with a lively rendition of the unofficial “anthem” of Calabria “Calabrisella mia”, regretfully, without its customary piano accordion accompaniment.

Before Josephine Gagliardi stimulated the audience’s appetite with images and descriptions of Calabrese delicacies, Sergio Sergi of the Dante Committee gave a brief presentation on the history and culture of Calabria.

The evening concluded with the traditional Calabrese farewell, which is both a wish and something of an admonition, “statte boni” (be good).

INTRODUCTION TO SAPORI DI CALABRIA

It’s impossible to convey a sense of place in a brief presentation; so this introduction to the Sapori “flavours” will be something of a flavour of Calabria as a place and a unique culture. I will speak of its origins in antiquity, of a couple of typical Calabresi of old and then use a couple of my childhood experiences, during my visits to my grandparents, to provide you with a sense of the people.

Finally, I will offer an explanation for the only aspect of Calabrese life that most people know and judge harshly, the ‘Ndrangheta.

Calabria is an ancient land, originally inhabited by the Italoi, descendants of the legendary King Italus of the Oenostri (wine growers from Greece). The region, often referred to as Magna Graecia – expanded Greece – was settled by Greeks during the 7th and 8th centuries Before the Common Era. (BCE). During the time of the Roman Republic, fugitive slaves from Lucania made their way south into the lands of the Italoi; the inhabitants of these lands at the tip of the “boot” were the first people to be called Italian.

During the reign of Augustus, the territory of the Italoi was renamed Bruttium, in Latin; as this place was settled by rebels (Brutti) who fled in large numbers from Lucania, which had been a Roman province long before the time of the Julio Claudian dynasty. (Lucania is where sausages were invented – lucanica is Latin for sausage).

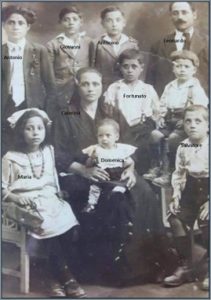

During this early period of the Common Era (CE), former Roman Legionaries were given land in Bruttium. The veterans tended to settle in groups; as a mark of respect they often took the name “cognomen” of their former commanding officer. The Sergii were one of the original hundred patrician families of Rome. This name reoccurs as commanding offices in historical accounts of military campaigns over several centuries. It was because of the veterans from their Leigions that pockets of people with the surname Sergi survived in several places in Calabria, notably in Melito Porto Salvo on the cost and Plati in the mountains of Aspro Monte (white mountain).

A recent study by Anna Sergi, “Chasing the Mafia” confirmed that there are over 300 or so people with the surname Sergi in the town of Griffith in NSW, which has a population of 27,000 of whom about one third are of Calabrese decent.

The Greek influence in Calabria is pervasive; Melito from honeybee, Plati (broad) and the modern name Calabria (beautiful land). Even the present spoken dialect (Griko) is heavily based on old Ionic Greek, the language of Homer. Its most famous son in antiquity was the pancratic (all contests) athlete Milo of Kroton (Crotone) who won the six events at the contest, in which included wrestling, running and javelin throwing at six consecutive Olympic Games held at the foot of Mt. Olympus in Greece. Milo is reputed to have carried a heifer down the course, killed it with one blow and eaten it, all in one day. Trying to split a tree asunder, he was caught in the cleft and eaten by wolves.

Two other famous Calabresi are particularly noteworthy, as they embody the main characteristics of the Calabrese character formed in antiquity. The first is the 14th Century figure, Leonzio Pilato, who translated Homer for Giovanni Boccaccio (the Florentine humanist author of the Decamerone – Greek for ten days of stories). The ability to read classical Greek had all but vanished in Italy at this time and it was largely through the veneration for the ancient texts by men like Boccaccio and his contemporary Petrarca that the body of classical Greek literature was revived. It is worth noting that, until the 14th Century, texts of classical Greek works, such as “The Iliad” existed only in Latin translations.

Edward Gibbon, the iconic English historian of Rome’s decline regarded Pilato as merely a “contadino” a peasant. In his Decline and Fall, Gibbon damns Pilato’s contribution with faint praise as: “a work in that age, of stupendous erudition in which he ostentatiously sprinkled with Greek characters and passages to excite the wonder and applause of his more ignorant readers”. (Part IV, Decline and Fall)

By all accounts of those who knew him, Pilato was a man of gloomy and antisocial temper: some say, unkindly, like many Calabresi. It used to be said that Calabresi men open their mouths for two purposes, per mangiare e bestemiare (to eat and to curse). Pilato died in 1366 after being struck by lightning, after having been warned repeatedly to remain indoors.

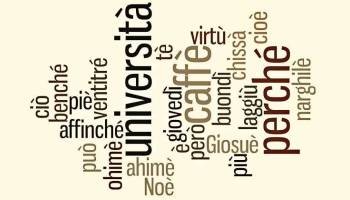

The other figure of cultural significance for the Italian Rinascimento is the poet Quintus Ennius, born in 239 BCE in Rudiae (near Spezzano Albanese). He is the author of the Annales patterned on the Homeric style, which hugely influenced Latin epic poetry and by extension, the first works written in Italian language during the 15th century. Regrettably, only fragments of his works have survived. He wrote that he had “three hearts” in Greek, a Latin and a Calabrese. I can identify with that and incorporate all three under the cloak of Australian.

Melito Porto Salvo, a honey sweet town and safe harbour has a population of 11,000 people in 2025. In 1914, the year of father’s birth it was about 2000. There was a train station, where my grandfather worked as a Capotreno, a parish church with two priests, a hospital run by Dottore Spatolitano – always in a starched white laboratory coat, and a Barracks of Carabinieri, six “militi -troopers” commanded by a Maresciallo (equivalent to Sergeant Major). They were needed to chase the briganti in the mountains – these days, they go by helicopter.

The most significant event in the history of the town of Melito occurred on 19 August 1860 when Giuseppe Garibaldi and one thousand Camicie Rosse (Red Shirts) landed after their military success in Sicily – “Lo sbarco dei Mille – the landing of the thousand” before moving North to face Royal troops and defeat at the battle of Aspromonte, where Garibaldi was shot in the ankle.

Melito was my father’s childhood home. My grandmother’s domestic skills were legendary. Donna Cata presided over a large kitchen with a huge table at its centre: the chairs, when not in use, were hung on hooks around the room. There was also lots of bergamotto in baskets as well as fichi d’India, grown on cacti that were found in fields and along roadways. These cacti were imported plants, so named after the “Indians” of America. Each year Donna Cata “faceve u maiale”, she used everything, including the britsles which she made into brushes. She was pretty scary; she yelled at me, as she regarded me as something of a simpleton, as I did not understand a word she said – she did not speak standard Italian and I no Calabrese.

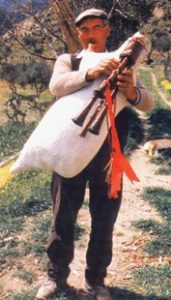

Calabrese culture is essentially that of shepherds. One Christmas I was enchanted by the zampognari and by the tarantelle danced by young and old alike. The wonderful Christmas carol, Tu scendi dalle stelle, O re del Cielo was composed by a Calabrese priest; I still here my father’s voice when I think of it.

One final reference needs to be made to the ‘Ndrangheta, the name made up of two Greek works andros (man) and agathos (the best), hence, the best man.

Unlike the hierarchical Mafia of Sicilia, the Calabrese equivalent has a flat structure, with the local clans being bound by tight ties of family and blood. This makes it impenetrable and firmly rooted in the very fabric of Calabria.

The Calabrese Anna Sergi, Professor of Criminology at the University of Essex in the UK, has written extensively about it and has explained the reasons for its existence; centuries of neglect by Government authorities, a feudal latifundist system of land ownership, and crippling poverty, in a harsh landscape. Calabria remains the poorest region of Italy. Yet Calabria has much to offer to the visitor; both of my sons have spent time there and have been made most welcome.

Yes, Calabresi describe themselves as having “u testa dura comu n’a pedru”, (a head as hard as a stone) but there are other sides to them. Tonight, we celebrate the food Calabria has treasured and given to the world; like the fichi d’India, Calabresi are prickly, difficult to reach and hard to penetrate, but once that is done, the centre is sweet and pure gold.

Article by Dr Sergio Sergi,

Committee

Dante Alighieri Society of Canberra