The lives of Antonio Panizzi and Edward Gibbon Wakefield intersected in London in 1827. The result of this event was a new city in the Antipodes and one of the world’s greatest libraries.

In order to fully unpack the words of the title, it is necessary to introduce these two men, then the events that brought them together. After a discussion of the new colony and the great library, we will conclude with what events placed the names of these two men in history.

To begin; Edward Gibbon Wakefield (1796 – 1862) was born in London in a Quaker family. His father, also Edward, was a distinguished surveyor and land agent. His paternal grandmother, Priscilla was a prolific writer of popular children’s fiction; as well she was one of the instigators for the introduction of savings banks for common people. Young Edward was sent to Westminster School, (one of the “Great Public Schools”), but was a distracted and unruly student. He left, in the words of his housemaster “spoiled for business and unqualified for a profession”.

Through connections, he obtained a post as King’s Messenger with the British Foreign Office. His task was to deliver confidential correspondence from Head Office in London to British Embassies abroad. He did this for a few years, including travelling to Brussels in 1815, before Waterloo.

In 1816, at 30 years of age, he eloped with 16 year old Eliza Pattle and they married in Edinburgh. The fact that it was Scotland was significant as its laws regarding marriage were somewhat different to those in England. On his marriage, £70,000 (about $AUD 10 million in 2024 money) was settled on him as her husband, with more to come when she turned 21.

They moved to Genova, where Edward was employed in a minor consular post and his living expenses were largely met by his wife’s family. The marriage produced two children, (Susan Priscilla, known as Nina and Edward Jerringham). Eliza died of complications two weeks after the birth of her second child. Wakefield returned to England and placed his children in the care of one of his sisters, Catherine, who brought them up-

In 1825, aged 38, Edward wanted to enter Parliament and so needed more money than he had obtained via his marriage. Through scheming and deception, on the 17th March 1826 he abducted from her school the 15-year-old Ellen Turner. He was aided and abetted in this by his brother William and by his mother. Ellen Turner was the heiress of a very wealthy Liverpool merchant. The couple were married in Gretna Green in Scotland and travelled in secret to Calais.

The couple and Mrs Wakefield senior were tracked down by two of Ellen’s uncles, a Solicitor and a Bow Street Runner (policeman), and brought back to England. If Ellen was deemed married, under Scots law, she could not testify against her husband. If she was not, then Wakefield could be charged with abduction and several other offences.

This case, known as the Shrigley Abduction caused a sensation.

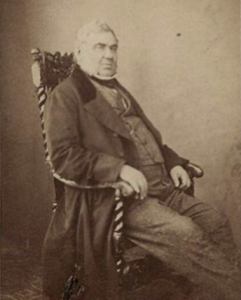

Now we need to meet the other player in this epic, or rather two more, the highly respected barrister and the young Italian political refugee. The young man’s name was Antonio, Genesio, Maria Panizzi. He was born in 1797 in Brescello, near Modena (Reggio Emilia). Steeped in a solid classical and legal education at the University of Parma, Panizzi practised law in his home town, but was also an active member of the Carbonari, a group that opposed the Bourbon control and repression of Italy. His activities resulted in a death sentence “in absentia”, and he fled, first to Switzerland and then in 1823 to England. With letters of recommendation by the poet Ugo Foscolo, who was also living in exile in Liverpool, Panizzi was introduced to the important lawyer and political figure Henry Brougham. In turn Brougham introduced Panizzi to Liverpool society, where he made a meagre living teaching Italian to private students. One of these students was the15 year old Ellen Turner.

When the Shrigley Case became such a sensation, Brougham represented the Turner family, while the defence of Wakefield was undertaken by a team of Scots lawyers.

Henry Brougham (1778 – 1868), later 1st Baron Brougham and Vaux, had become a celebrated jurist and advocate in 1820 of Queen Caroline of Brunswick. The case against her was brought by King George IV to dissolve his marriage, so he could marry – horror – his Catholic mistress. The Court was persuaded by Brougham’s defence and found in favour of the Queen. Brougham was also an Abolitionist which was a difficult moral stand to take in Liverpool, which was the centre of the slave trade. He was also a reformist of Courts and Parliament and an ardent Whig in the Tory dominated political life of the time. On one occasion he spoke in the House in favour of the Reform Act 0f 1832 for six hours without pause!

He had studied mathematics at university and had a practical bent; the light two-horse drawn carriage he designed carried his name – the Brougham.

Panizzi, drawing on his legal expertise, acted as Brougham’s junior. He fed him references and quotations and case studies from the Edicts of Justinian, Roman Law and Ecclesiastical and Canon Law. He also suggested the involvement of Parliament. The poor Scots lawyers were routed by these legal fireworks. The required Act of Parliament passed and the marriage was dissolved. Wakefield was imprisoned for three years in Newgate Gaol and his accomplices also received custodial sentences.

Brougham persuaded Panizzi to move from Liverpool to London to take up the position of Lecturer in Italian at the newly minted University of London. Panizzi did this and also engaged an impoverished fellow countryman to help with the teaching. It was Benedetto Pistrucci (1783 – 1855), a Roman engraver and maker of medals and cameos. Subsequently, he was employed by the Royal Mint (he could not be appointed as Chief Engraver as he was not a British citizen). He made history by engraving the St George and the Dragon motif which is still used on English sovereigns.

But back to the story begun in 1826, which we left off with Edward Gibbon Wakefield in Newgate Prison, where he stayed until 1830. Perhaps drawing on his Quaker upbringing of social reform, to provide relief for the poor, the mercurial Wakefield reinvented himself as a colonial reformer. He read various accounts of the Colony of New South Wales; Charles Wentworth’s A British Settlement in Australasia and a work by the French Canadian Robert Gourlay on the problems of the Colony of Upper Canada.

The result of his reading was a series of “Letters from Sydney”, originally published in the London Morning Chronicle. Wakefield posed as a disgruntled settler in the Colony of New South Wales. He complained of mismanagement caused by grants of large tracts of land. He proposed the sale of Crown Land instead, in small parcels, at “a sufficient price, fixed and modest”.

The proceeds of the sale would pay for sending free emigrants from the UK. They would be selected by gender, unlike the convicts who were mostly men, and represent a cross section of British Society, namely labourers, artisans, tradespeople and capitalists. The key principle of the scheme was private enterprise: the profits from the sale of the land to capitalist investors would finance the settlement of the colony by free men with skills and ambition. What was left out was religious extremism, South Australia became “The Paradise of Dissent”.

This pastiche was taken at face value by Robert Gouger, who published these letters in book form in 1829.

At much the same time as Wakefield was in Newgate, (1829) Gouger was also in prison for debts owed to various printers. Gouger became enamoured of the “Wakefield Colonization Scheme” and persuaded the likes of the economist John Stuart Mill, the social reformer Jeremy Bentham and the surveyor Colonel Robert Torrens to form the National Colonization Society. By 1831, Lord Howick, Colonial Secretary was won over by the idea of abolishing land grants and selling land at 5/- per acre. Not surprisingly, given their personalities, Gouger and Wakefield soon fell out over their involvement in the South Australia Land Association, but the province of South Australia was established by an Act of Parliament in 1834. On 26 December 1836, at the old Gum Tree at Glenelg, on a searingly hot day, Governor John Hindmarsh proclaimed the new colony.

Gouger’s legacy, after a brief period as Colonial Secretary in Adelaide, was the name given to a main artery of the meticulously planned city, which intersects with King William Street. Adelaide was named for the wife of King William IV. Gouger also founded the first Masonic Lodge in South Australia.

But what of our romantic hero, Edward Gibbon Wakefield? The rest of his life is a series of more or less mischievous and half-baked involvements in colonizing ventures in both Canada and New Zealand. His mantra was: “Possess yourself of the soil and you will be secure”. Wakefield was (all briefly) Director of the New Zealand Company; had a stint in Canada where he was involved with rebellions in both Lower and Upper Canada, where he became an MP for a year.

He was soon back in New Zealand with his brother Felix (who had abandoned his wife and the youngest of his eight children in Tasmania; the other children were farmed out to the Wakefield sisters to bring up). Other settlers in New Zealand described the brothers in 1851 as “the worst men in Canterbury”. Eventually, after manipulating the Colonial Government of New Zealand to pay his considerable debts, Wakefield left politics, became ill and died at the age of 66. As George Orwell noted “at 50, everyone has the face he deserves.

His legacy, in addition to the “Wakefield Scheme for Systematic Colonization” includes place names such as Wakefield River and Port Wakefield in South Australia. The main street of Adelaide, Wakefield Street, is actually named after his brother Daniel, who helped draft the legislation for the establishment of the colony. There is also a marble bust, of Edward Gibbon Wakefield in the High Court building in Wellington, New Zealand; in 2022 the Wellington Council called for its removal.

There we leave Wakefield, political theorist, Member of a couple of Colonial Parliaments, Diplomatic Agent, fantasist, sexual predator and schemer. His talents lay in visualizing dramatic plans and grandiose schemes, ignoring detail and in persuading people to become involved with his castles in the air. He was a salesman, propagandist and the consummate flexible politician.

What was Antonio Panizzi doing while Wakefield was up to his shenanigans in the colonies? What is the legacy of this Italian revolutionary lawyer, scholar, bibliophile and prince of librarians?

His patron Brougham, now Chancellor of England, helped Panizzi to secure the post of Extra Assistant Keeper of Printed Books in the British Museum, which then housed the enlarged collection bequeathed by Sir Hans Sloane, and all books owned by the nation, some 200,000. Panizzi worked to split the library from the Museum. Having in mind the great libraries of the European capitals, such as Berlin and Paris, Panizzi convinced the government to pass the Copyright Act of 1842, ensuring that one copy of every book published in England should be deposited with the British Library. During Panizzi’s time the number of books in the National Collection almost trebled.

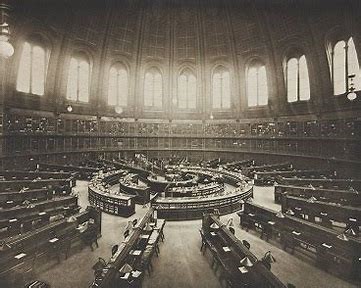

Based on Panizzi’s design, the architect Sydney Smirke built the Domed Reading Room, an engineering marvel which opened in 1857 and remained in use in Great Russell Street until 1997, when the British Library was moved to its new site at St Pancras. Conan Doyle (and his creation Sherlock Holmes) were regulars at the Reading Room. Karl Marx wrote Das Kapital under its dome – notably, in Chapter 33 of this work, Marx has a scathing criticism of the “systematic colonisation” methods of Edward Gibbon Wakefield, for the dispossession of First Nations Peoples from their lands through capitalist exploitation.

Panizzi battled many criticisms, many of which were due to his Italian origin including one which was actually reported in The Times, “he was seen in the streets of London selling white mice”.

Panizzi’s Ninety One Rules of Cataloguing became the basis of the ISBD of modern cataloguing. He was a friend of both Prime Ministers, Palmerston and Gladstone and orchestrated the visit by Giuseppe Garibaldi to England, where the Italian patriot was mobbed like a pop-star, even having a biscuit, still on sale today, named after him. The measure of the Panizzi can best be summed up by this statement he made explaining the role and purpose of the British Library:

“I want a poor student to have the same means of indulging his learned curiosity, of following his rational pursuits, of consulting the same authorities, of fathoming the most intricate enquiry as the richest man in the kingdom, as far as books go, and I contend that the Government is bound to give him the most liberal and unlimited assistance in this respect.”

Panizzi’s editions of Boiardo’s Orlando Innamorato and Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso are still regarded as works of refined scholarship. There is a bust of Antonio Panizzi in the British Library – no one has called for its removal!

Article by Sergio Sergi

Bibliography

Edward Miller Prince of Librarians The Life and Times of Antonio Panizzi of the British Museum, The British Library 1988.

E.G. Wakefield A Letter from Sydney Everyman’s Library No 828 M Dent and Sons London 1929