I Promessi Sposi (the Betrothed)

Alessandro Manzoni writes in beautiful prose and his historical novel, I Promessi Sposi (the Betrothed), is rightly celebrated as a gem of Italian literature. It was written in the nineteenth century and first published in 1824.

The couple at the centre of the story, Lucia and Renzo, lived two hundred more years before that, in a small village near Lake Como. Renzo farms a small plot and Lucia lives with her widowed mother. The two are deeply in love and they plan to be married, and thereon hangs a tale.

In the years in which their lives are set, Lombardy was a colonial possession of Spain and the first villain we meet is the arrogant and dissolute Don Rodrigo. He is the local “baron” and has lusted after Lucia for some time and will stop at nothing.

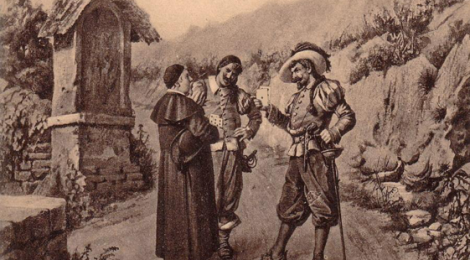

It is for this reason that the timorous Don Abbondio, the village priest, finds himself accosted one evening in a country lane by two of Don Rodrigo’s thugs. These bravi leave him in no doubt as to what will happen to him should he marry the couple. Don Abbondio is ill equipped to face such a challenge:

“Don Abbondio (our reader will have already discerned) was not born with the heart of a lion. From his earliest years, he was compelled to recognise what a misfortune it was to be, in those times, a creature without claws or fangs, yet which feels disinclined to be devoured …Our Abbondio was neither noble nor wealthy; and courageous, even less. He had thus realised, perhaps before reaching the age of discretion, of being, in that society, like a terracotta vessel compelled to travel crowded together with a host of iron jars.”

Events of the novel follow one another in a roller-coaster of good and evil fortune as the young couple are compelled to flee in separate directions and as they struggle to find each other again through kidnappings, betrayals, violent uprisings, wars, invasions, exiles and an outbreak of the plague. A lot happened in seventeenth century Italy.

Manzoni weaves together history, philosophy, theology and social commentary. However he is at his best in the incisive pen portraits he sketches for his characters. Often, we find ourselves sharing their inner thoughts. We learn for instance of Fra Cristofaro, a saintly Franciscan monk who devotes himself to the cloth in penance for youthful folly which leads to the death of a beloved mentor.

Gertrude, the Nun of Monza, is another such character, whose story introduces us to the social realities of wealthy families of the era. As a teenager she carries the pride of her illustrious family. Yet her wealth is her misfortune. Her father and family have long decided her future. The family patrimony will not be divided to provide the generous dowry that would be necessary for her marriage. No, from birth, she has been made to understand that her future will be as a nun. It is a future to which she is singularly unsuited. We see her desperate struggles to evade her fate, as she comes to understand that it is not what she wants for herself. But we see also the web in which her manipulative father has entrapped her, winding her ever tighter until she herself publicly and forcefully proclaims her free desire to enter the nunnery. We meet this tortured character as her life intersects Lucia’s.

As Alessandro Manzoni continued to unfold his work his aspirations for his novel became aspirations for an Italian language reborn. He wished to reunite the written language with living spoken Italian, from which it had for so long been sundered. Faced with the many dialects of Italian he settled on Tuscan as his preferred vehicle to embody this project. In its 1840s edition, I Promessi Sposi was comprehensively reworked, including with the assistance of the Tuscan governess of Manzoni’s children, Emilia Luti. Like Dante centuries before, his literary project became the proof of what was possible for the renewed Italian he imagined. As Migliorini observed:

“… the novel did much to achieve what Manzoni set out to do: to bring the written language nearer to the spoken and to deal a deadly blow to the rhetorical frills which for centuries had disfigured Italian literature.” [Bruno Migliorini, The Italian Language, translated by T. Gwynfor Griffith, p 364]

I Promessi Sposi is available as a free ebook in the original Italian at https://www.liberliber.it/online/autori/autori-m/alessandro-francesco-tommaso-manzoni/i-promessi-sposi-edizione-a-mondadori-1985/ A beautifully narrated audiobook, also in Italian, is also available at the same link. Many English translations are available including a Penguin classics edition.

Michael Curtotti has written a longer article on Alessandro Manzoni and I Promessi Sposi which can be accessed at https://beyondforeignness.org/8881

Michael Curtotti